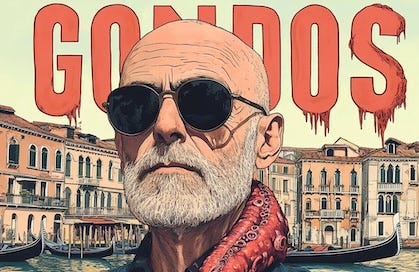

The novelization of the major motion picture GONDOS, serialized every Wednesday and Thursday. For more information and to get caught up, click here.

PREVIOUSLY…

The three gondo pilots hunted the schifosi through Venice. Millie was forced to kill one in self-defense. All alone in front of the Marco Polo house, she moved in closer to inspect the corpse.

Meanwhile, Guy and Benny, having zipped down the Grand Canal in pursuit of the animals, discovered them laying siege to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, where hundreds of art lovers attended a buzzy late-night opening…

“Stay down! Get behind the pillars!” Guy shouted to the crowd on the Guggenheim’s terrace, as he and Benny raced in on their gondos, side by side.

They hurtled forward behind a monsoon of bullets. Tentacles spiraled at them from all directions, swishing like scythes at their ankles and heads.

The men swiveled and skidded in their gondos to dodge them. They leaned left, leaned right, heaving their rudders and throttles to zigzag erratically and evade each attack. The necks and tails of their vehicles flexed and swung sideways, clenching and unclenching, kicking up their own spray amid the sprawl of writhing bodies, the splashing of so many belligerent arms.

The two men squeezed their triggers the entire time.

Rondack nailed two or three on his first pass—then whirled around to watch one of the bodies bleed out.

“That was awesome!” Benny shouted, swooshing back to enter the scuffle again. He’d killed a couple, too—punching so many bullets through one of them, and at such close range, that flesh had burst off its body in a pinkish mist.

“Clear them away from the museum!” Rondack instructed.

They mowed through a second time. They took down several on the periphery and attempted to barge their way to the foot of the terrace. But the conglomeration of skeefs there was harder to penetrate, packed in tightly, like pigs feeding at a trough. Benny winced as, having spun around to flee a vortex of outstretched tentacles, he found himself weaving between slabs of human flesh, bobbling at the surface.

Rondack blew past him, firing mercilessly, trying to open a path. Catching one in the throat as it reared out of the water, he watched the animal go limp and sink beneath the surface again.

But then it bobbled back—only momentarily stunned.

Guy fired again, for longer. This seemed to do the trick.

He quickly tagged an animal on his left and, right away, another racing in on his right—then spun his gondo a hundred and eighty degrees again to finish off the first one, as it too had apparently withstood the gunfire and resurfaced in a daze.

“Look out!” Benny shouted.

Guy hadn’t seen a third one coming. Its open mouth scraped the surface of the canal right behind him. The skeef approached teeth-first.

Guy swiveled and saw it—just as the animal was suddenly silhouetted against an incandescent flash.

Two rows of ragged, bloody punctures opened across the base of its head, just above the tangle of tentacles streaming off its neck. The skeef was shuddering—getting absolutely plugged.

Millie scorched into view on her gondo, still firing her guns at the animal, then swerved sharply to give its now-flaccid body a final kick with the tail of her craft.

“Got him!” she hollered.

It was her turn to rescue Guy Rondack; she’d arrived just in time.

Guy put his fist on his heart to thank her.

She had shot the animal so many times, and perforated its neck to such a degree, that now, as Millie flew past it a second time, the head dislodged and ripped clear off the body, joggled loose in her vehicle’s wake.

The gondos regrouped in the center of the Grand Canal. Rondack arranged them in a V and gave a signal. They shot toward the Guggenheim again.

But this time, when the boats opened fire, the skeefs shucked and scattered—their tentacles contracting and pulsing outward, propelling them away. The three gondos kept after them, but their bullets were only riddling empty water. It was like fighting a reflection—a fluid array of swift, glinting lights.

Until then, the animals had seemed governed almost entirely by a savage compulsion to feed. But now, their awareness expanded beyond their prey. They were reacting to the gondos with more alacrity and more viciousness—pounding at the vehicles, learning how to fight.

Five or six minutes of the battle passed this way. A few hundred seconds that felt like an hour.

Then Benny shouted, “Shit, we’ve got climbers!” and Millie’s stomach dropped.

Four animals were hauling out of the canal onto the museum’s steps, clambering over one another like crabs escaping a bucket. Their shorter tentacles scraped the terrace clean of people ahead of them, shaving bodies off like so many hairs.

Millie watched as two of the creatures happened to snatch two different parts of the same man, each oblivious to the other. One bit down on his calves while the other clutched his neck in its tentacle, tugging the crown of his head toward its jowls. As both animals pulled, the man screamed and mewled and caterwauled in anguish. These sounds had a distinctive undertone though, immediately recognizable to everyone around him. It was Michael Stipe. A moment later, he was cleaved in two.

More skeefs made landfall as the first ones, gasping, returned to the canal to breathe. One of these newcomers mistook the cast-iron sculpture at the center of the terrace—a black human form on horseback—for a warm body. It coiled a tentacle around the figure’s outstretched arms and wrestled with the object in frustration, unable to rip it off its moorings.

Finally, the animal’s other long tentacle rocketed out of the water and the two, working together, snapped the sculpture free. The horse came hurtling down the terrace, fast: an avalanche of iron. Anyone in the sculpture’s path was pushed downhill—where the fevered conflagration of other creatures raked them into the water, into their mouths.

“It’s not working!” Millie shouted, still firing into the fray.

Her energy was flagging, while the skeefs seemed inexhaustible. Even with all their firepower, the gondos seemed to merely be interrupting the animals; she did not see a way to make them stop.

Millie bolted away from the melee momentarily to catch her breath, vigilantly scanning the water behind her for stragglers.

The last thing she expected to see was another boat. But there it was: the trim silhouette of a lone gondolier, rowing toward her down the Grand Canal.

Alessandro had gotten the text nine hours earlier. He’d been at the squero—the gondola maintenance yard—helping his uncle after work to strip the flaking paint and mold off the hull of an old gondola, fixing the craft up for Alessandro’s deadbeat cousin who, per usual, needed a job.

The message was from Dino Simonetti, the aging capo of the gondolieri guild—who’d sent it immediately after getting the Magistrate of the Water’s apprehensive phone call from the doorway of ELAINE.

“Change of plans,” Dino’s text to Alessandro read. “There’s a situation. I need a good man to make yarn tonight—and you’re my best.”

Alessandro sighed. In his mind, he was being taken advantage of; it was Dino’s flattery that gave it away. Clearly, whichever gondolier had been assigned to do the traditional patrol that night had faked sick or gotten too coked up to row, leaving Dino in a bind. And yet, even realizing this, Alessandro was not bold enough to refuse this last-minute assignment from his boss—which is exactly why Dino knew to thrust the job on him.

Alessandro slapped the dust and paint chips off his gondolier’s uniform. “Dino needs me to make yarn,” he told his uncle. His uncle—a gondolier himself once—nodded and offered him an extra scarf and a warm pair of gloves.

Once out on the water, Alessandro told himself he wouldn’t row that hard—a subtle protest, carried out in private, in the unbroken solitude of the night. Still, by 2 AM, he had covered as much ground as he always did when he made yarn—and had ever since his earliest days of doing those patrols, when he was younger, more dutiful and more eager, and his muscles were slower to ache.

He was drifting down a tributary of the Guidecca canal, looking back at the city center, when suddenly appeared a surreal sight: flocks of waterfowl wafting out of the skyline like an exhalation. It was as though all the birds in Venice had lifted off from their scattered resting places in a simultaneous flurry and fled.

Gradually, in the hour that followed, an unsettling feeling overtook Alessandro. He rowed faster, with purpose, not knowing exactly why. He barreled due east, then banked north through the Dorsoduro district’s spindly waterways, toward the Grand Canal.

Suddenly, a loud, percussive clatter ripped across the water.

Gunfire. Alessandro recognized it from films.

Steadfast, sweating, he pounded downstream through the heart of Venice. He passed the Grassi Palace, under the Accademia bridge, then squinted at a disturbance in the distance.

He saw the arms first.

The gyre of arms.

They reared out of the darkness—corkscrewing intermittently through the columns of empty space illuminated by the Peggy Guggenheim Collection’s spotlights. He watched them curl and tauten in the air like earthworms. He watched them whir like blades.

The arms battered at the architecture. They clasped wriggling, living things.

“Go, get out of here!” a woman screamed at Alessandro from the darkness ahead of him.

He could barely make her out: upright on the water, piloting a sleek, silver boat that was roughly the size and shape of a gondola but fleeter, fiercer, futuristic—a machine as unfathomable to him as the grotesque scene at the museum behind her. A machine with… were those guns?

“Go! Quick!” she hollered again. She leaned to one side, and her boat swirled psychotically back down the canal, like a strand of tagliatelle swishing in a boiling pot.

But Alessandro didn’t listen.

It was instinctual: His hands choked up on his oar. He rowed toward the danger instead.

“Go! Quick!” Millie hollered at the gondolier and, swiveling her gondo, streaked back toward the museum.

The bedlam at the foot of the terrace was relenting as the skeefs appeared to be running out of prey. The tight knot of creatures feeding there seemed to slacken. Individual skeefs broke off in all directions, knocking the dead ones out of their way as they dispersed to probe other areas of the canal.

Two locked onto Rondack, who execute a fitful series of evasive loops.

Benny had picked up another. It ripped at the water behind his gondo with its upper tentacles, gaining fast.

Far on the periphery, meanwhile, a trio of skeefs was picking up speed—racing upstream toward the gondolier who, instead of fleeing, was now rowing unwittingly straight at them in the dark.

Millie spotted these last runaways out of the corner of her eye while spinning to dodge a burst of tentacles on her right flank. In one motion, she jolted her rudder upright to stop her rotation and pulled back on her throttle to speed after them, upstream.

The gondolier panicked. He could not make sense of what was coming at him: the woman on her inconceivable vehicle, the three shapes surging violently through the surface of the water that seemed to be chasing—all of it approaching at breakneck speed.

Alessandro hunched down in his gondola, wrenching his oar back with maximum leverage to turn his boat and retreat.

Millie hunched forward in her gondo, bearing down on the three monsters bearing down on him.

Alessandro’s long, stiff, wooden craft was only barely beginning to swivel when he recognized that it was too late. They were only meters away.

“No!” Millie cried.

She didn’t understand what happened next.

The animals missed him.

No. They swerved around him.

All three had stopped abruptly right in front of his prow, as though colliding with some invisible, unmovable force. The stunned animals wriggled momentarily in place. Then their bodies crumpled like paper and uncrumpled instantly, oriented now on a marginally different course. All three accelerated again, scuttering straight past Alessandro, on either side of his boat.

They’d hurtled by him at such close range that his uniform was now saturated with their fetid spray. His gondola rocked sideways in their wake. He struggled to keep his balance, replaying it in his head.

His gobsmacked gaze met Millie’s. And her eyes went wide wide, too:

You again.

But just then Benny yowled “Fuck off!” in the distance and Millie’s head whipped around to see, further downstream, the tail of his gondo ensnared in the arms of a skeef.

While chasing the skeefs that were barreling toward Alessandro, Millie had not noticed a fourth animal gaining on her. But Guy—his weapons spraying the canal in front of the museum, his vehicle and his body both contorting adroitly to skirt a ceaseless onrush of arms—somehow did register the creature going after Millie. He had let his finger off his trigger just long enough to shout “Help her!” at Benny, who spun his gondo around and took off.

But the skeef tailing Millie—which Benny was now tailing—had suddenly bounded backward and attacked. The two long tentacles at the center of its back had shot forward to seize the tail of Benny’s gondo, and were now struggling to drag the boat backward, to its mouth.

Benny couldn’t fire at it; his weapons faced the other direction. So he was throwing all his weight onto the throttle, trying to pull his gondo away. But clenched in the squirming coil of the animal’s arms, his vehicle only sputtered forward slightly, sporadically. The engine hiccupped and stalled as the skeef heaved the vehicle steadily closer to its maw.

It got closer—four, then two meters away. The animal began passing the gondo from its longer arms into shorter tentacles flaring off its neck. These arms prodded and slid over the gondo’s smooth surfaces, fumbling for a grip.

Failing, they began to punch at the hull instead. They snapped the rudder rod in two at the rear of the craft, then struck further up the length of the boat, pummeling the edge of the cockpit where Benny was standing.

Then the skeef hauled its head out of the water and crashed down onto the gondo’s tail.

The front half of Benny’s gondo lifted out of the water in response to the creature’s weight, vaulting up like the end of a see-saw.

He scrambled backward, cowering onto the gondo’s long, flexible neck as it rose out of the canal—trying to put as much distance as possible between him and the monster.

Slowly, the skeef’s pitch-black eyes opened. And this sent Benny over the edge.

“Fuck off!” he screamed at it. “Stop looking at me!”

He had no way of knowing that, under the surface, the skeef’s two, longer dorsal tentacles had released his boat and were extending forward under the water, stretching along the entire length of his gondo, and twisting upward again.

Their tips resurfaced without a sound, without a splash. Then the two arms busted into the air right behind Benny, as he continued to bob on the upturned bow of his boat. They unfurled behind his back like a pair of wings, dripping and glistening in the flashes of Guy’s gunfire behind him and in the moonlight beyond.

“Look out!” Millie screamed, careening into view.

But at that very moment, one of those tentacles cinched around Benny’s neck and the other spiraled around his waist. Then both torqued in opposite directions, snapping his spine.

Millie wailed and opened fire. Eyes closed, she did not see the skeef’s head pucker and convulse. She did not see its long arms go lame and release Benny’s body—which, suddenly structureless, fell sideways off his gondo and sank.

All she saw when she opened her eyes was the shredded carcass. The empty, rocking boat.

Millie turned behind her just in time to watch Alessandro quickly passing into the darkness upstream, rowing his gondola away. Downstream, meanwhile, the skeefs were decamping from the ruins of the museum and barreling back to sea.

Millie spotted Guy idling in front of the Guggenheim and went to him. He was soaked with canal water, soaked with sweat. He’d never stopped battling—not even for a second. Now, he simply stared at where the herd had just disappeared, partly out of vigilance and partly—this was clear to Millie—out of a refusal to look in the opposite direction, where his friend had just been killed.

Millie didn’t want to look either. Benny had died fighting to save her.

She stepped off her gondo and scrunched next to Guy on his, then laid the side of her head on his chest.

On the steps of the Guggenheim, the few survivors were stirring from their hiding places. A young man—both his shoulders broken, his shirt bloodied and torn—hollered down at the two of them in the canal: “Is it safe?”

“They’re gone,” Guy said, coming back to life. He cradled the back of Millie’s head, holding her even closer.

“What scared them off?” the man said.

Guy looked down at Millie unsurely. Millie looked up at Guy.

“They didn’t leave because they were scared,” she whispered. “They left because they were full.”

…in Chapter 12!

“Before tonight,” Alessandro told the Magistrate, “I thought the legend was preposterous.”

“The truth often is.”

Enjoying GONDOS? Tell a friend, tell a thousand friends, tell your home owners association, tell your bowling league. Broadcast your enthusiasm on social media! Talk about it on your podcast! Together, we can make GONDOS a global sensation!!!

Due to its universal importance, food has always held a special place in history. The perfect product for both of us: https://retrobowlonline.co/