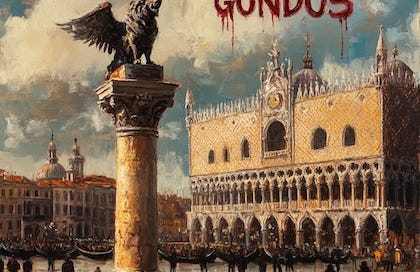

The novelization of the major motion picture GONDOS, serialized. For more information and to get caught up, click here.

A NOTE TO READERS:

GONDOS will pause next week to give an influx of new readers a chance to catch up.

Then...buckle up as we binge all of Part Three, with the five final chapters of GONDOS released daily, Monday-Friday, October 7-11!

It’s going to be a balls-to-the-wall blockbuster event, as together we ride the lightning all the way to the end.

You won’t want to miss the stunning conclusion of…

GONDOS: THE NOVELIZATION OF THE MAJOR MOTION PICTURE GONDOS

PREVIOUSLY…

The Battle of the Biennale was a bloodbath. The gondos were overpowered. Scores of Guggenheim patrons were slaughtered. Benny Baldwin lost his life.

Meanwhile, Alessandro—called to do night patrol by Dino (at the behest of the Magistrate of the Waters)—found himself unwittingly trapped in the fray. Three skeefs charged his gondola but, at the very last second, and with Millie looking on in disbelief, the creatures inexplicably swerved…

“Dino!” Alessandro called, pounding the door of Bar Forcolaio. The lantern above the entrance was no longer lit, but he could see the lights on in the old capo’s apartment upstairs.

Alessandro had spent the last several hours sitting and pacing in a nearby calle, as far from the Grand Canal as he could possibly get.

Even as his shock subsided, his thoughts strained to recohere. The image of those three monsters careening at him would, no doubt, remain stamped in his consciousness for the rest of his life, but whatever had happened next instantly turned to vapor in his mind. What had Alessandro done to shield himself, to ward the creatures off?

Why had they swerved?

He could still smell the scummy water they’d kicked up when they passed, still feel the needlelike sensations of their spray. His gondolier’s uniform was drenched. And, cowering in the alley, he’d noticed a portion of his pants matted to his thigh by something more acrid, too.

Alessandro had wet himself. Maybe. He couldn’t be sure.

“Dino!” he called again.

He was ready now to make his report—to attempt, somehow, to tie down the madness of that night with words.

Bar Forcaliao’s door opened inward, away from Alessandro’s fist as he knocked, and there was Dino, eyes sagging with exhaustion; his scant, white hair a mess.

Before Alessandro could speak, the old man raised one finger and stepped aside to reveal an elegantly dressed woman with a drink in her hand, rotating her stool to face Alessandro—slowly, regally, like a work of art on display—directly under her own portrait, framed above the bar.

“Alessandro Munari, is it?” asked Alessia Barbarigo, the Magistrate of the Waters.

It was surreal to hear her speak his name.

“Take a walk with me.”

Finishing off her digestivo, she stood and breezed past both men, out the door.

The gondolier froze and looked at Dino, who only nodded toward the Magistrate with his chin, reinforcing the chain of command.

“We didn’t intend to put you in danger,” she said. “We owe you an apology. But we also owe you an explanation.” She placed a hand on Alessandro’s shoulder, and her expression softened. A hint of her old pop-star luster washed over her face, triggering in Alessandro a Proustian sense of safety—even a pang of desire; like every other boy his age, he’d had her hit version of “All the Young Dudes” on cassette single and her picture pinned on his bedroom wall.

“Please,” the Magistrate said. “I have more emergency business to attend to at my office in Piazza San Marco—or so they tell me. And it’s dark out. Escort me. Please.”

“Of course, Comandante.”

The two set out into the night.

“Let’s start right there, in fact,” Barbarigo told him. “Why do you think you call me that: ‘Comandante?’”

Alessandro balked. He’d never considered it.

“Isn’t it odd? Venice is not a militaristic society,” she said. “Rather than repelling invading armies, our ancestors only had to repel the tide—the very same water that sustained us. And yet, that project—the arduous and perpetual maintenance of our sacred pact with the sea—served as a moral equivalent of war: the same solidarity and civic pride which other societies forged in combat arose, here, amid the labor of persevering Venice’s serenity, defending against the water, keeping our Republic dry. You know all this. What you don’t know is that, from time to time, we had to band together to defend against certain creatures that spawned in that water, too.”

Alessandro’s eyebrow arched slowly. “Schifosi,” he said.

“Schifosi,” Barbarigo repeated. “Indeed. A fish, but not a fish: a monstrous pest with a snout like a wolf, a mane of tentacles blazing from its neck, and two horrid and brawny arms on its back. An animal whose shocking and discordant appearance must have so outstripped our ancestors’ powers of comprehension that the early Venetians could only name them schifosi—’the disgusting ones.’ Because it was only their disgustingness beyond all measure that could be described.”

They were passing by the Church of Santa Fosca now, crossing over a wide bridge onto the Strada Nova. At this hour, all the thoroughfare’s shops, cafés and gelaterias were encased behind their metal gates. Other than a few rats skittering in the shadows, Alessandro and the Magistrate had the street to themselves.

“Before tonight,” Alessandro said, “I thought the legend was preposterous.”

“The truth often is,” she insisted. “I remember, as a child, my grandfather explaining to me what I am about to explain to you and feeling the same way. But you’ve studied our history, yes? To pass your guild’s exam and receive your gondolier’s license…? You know these years: 961? 1299? 1310? 1535? 1600? I could go on. Tell me, what is their significance?”

“Floods—historic ones. Devastating.”

“Made doubly devastating by infestations of schifosi. Those animals have poured into Venice unpredictably during periods of exceptionally high tides, sometimes centuries apart and—”

“Not those same monsters I saw tonight!”

“No, not the same exactly,” the Magistrate said. “Something is transforming them now, Alessandro. The lagoon is changing. The animals you saw are larger and more powerful. Still, they are recognizable. The schifosi have always been ferocious. This is not new.”

As they walked, the Magistrate fished through her purse until she found a battered, hand-rolled cigarette. Now, she stopped and looked at Alessandro, who did not right away grasp that this was her way of asking for a light. He took his Zippo from his pants pocket but found, with some embarrassment, that it had gotten too soaked to spark. It took many attempts before he could produce a flame.

Alessandro’s nose wrinkled. The woman was smoking a joint.

“I’m entitled,” Barbarigo said without a hint of defensiveness or unease. “But you, no. You must stay clear-headed. You are learning something here.

“For as long as people lived in Venice,” she went on, “there were stories of these creatures—all easily dismissed. But in the winter of 1310, a fantastic flood overwhelmed the city, and the first true infestation occurred. The animals invaded. They overtook Venice’s lowest-lying point, which is….?”

“Piazza San Marco,” Alessandro answered obediently.

“Many Venetians died in the piazza night, trying to hold that inundation of schifosi in the piazza at bay. And the creatures might have ravaged even more of our ancestors, and dispersed through the entire city, had St. Mark himself had not intervened to protect us.”

“Okay, sure, divine intervention,” said Alessandro snarkily.

“Divine intervention.” The Magistrate wasn’t amused. “Indeed, with a blazing flash of holy white light—and this is exactly how my grandfather told it: with a blazing flash of holy white light—St. Mark, our city’s patron saint, cast down his power from the sky and sent it surging through the piazza’s floodwaters to destroy the animals. Thus, the city was saved. The next morning, our fishermen towed the burned carcasses of those creatures out to sea.”

“A lightning strike, you mean,” Alessandro told her. He was accustomed to decoding the vestiges of Christian magical thinking prevalent in his parents’ generation. “Lightning struck the water and electrocuted the animals.”

“Not a lightning strike. A miracle. I am telling you a story,” the Magistrate shot back. “A legend—precisely as it’s been told for thirty generations. Don’t act so smart.

“Understand,” she continued, “the ancient Venetians knew that, if these monsters returned, and if their population swelled further, the canals would become treacherous, impassable. Our city was a crossroads, a global marketplace—we made our living on the water. The threat was therefore existential. Everything our Republic had built could be upended by an awful fish–a disgusting, awful fish.

“And so, while the work of defending Venice against the sea has always been shared by every Venetian, there were, let’s say, special duties assigned to certain citizens as well. These elite individuals were secretly enlisted under the auspices of a new government authority to be a kind of navy…”

“The gondolieri,” Alessandro blurted.

“Good boy,” Barbarigo said. “A navy which would monitor the canals and stand guard over them—and, when necessary, rise up to stamp out these infestations of schifosi before they could progress. The health and the security of the lagoon have always been the purview of the Magistrate of the Waters, Alessandro. And that includes this work. You, the gondolieri, truly are my first guardians and sentinels…”

“...and you, our Comandante,” he said, catching on.

“Exactly. We would not be blindsided again! After that first infestation, we initiated our nightly patrols—our yarn-making—to detect the arrival of these dismaying monsters in the canals before their numbers grew out of hand. When I told Dino tonight to send his best man to make yarn—to send you—that is merely what I had in mind: a mission to investigate, to observe. I never imagined there’d be so many of them here already, nor how grossly they’ve metamorphosized, how menacing they’ve become. This is my apology to you.”

“Accepted.”

Barbarigo didn’t acknowledge him. She examined the joint she was smoking and lifted it again to her mouth.

“Meanwhile, over time, in addition to our yarn-making, we established other protocols and tactics. A strategy was perfected for driving out the schifosi when the high water came. The gondoliers learned to flush them out of every corner of Venice, driving them through the canals and into the floodwaters in Piazza San Marco. There, the gondoliers would have the schifosi trapped, yes? Contained! Spears were distributed. The slaughter began.”

She waved her hand, as though it were that simple: lure, trap, spears, slaughter—that was that.

It was ludicrous. But clearly, her story had concluded. She took another puff.

“But Comandante,” Alessandro said respectfully. “That has to be part of the legend too, correct? I have trouble believing that those animals could be exterminated by only the gondolieri.”

“Ha, of course you don’t believe it!” she barked. She addressed herself to the joint again and held the smoke for quite a long time, looking him up and down until she finally exhaled. “Dino speaks highly of you. He says you are the exception among his gondoliers—a thoughtful young man, a sensitive man of integrity. But your generation, Alessandro: it depresses me. You are rudderless.”

“Rowing a gondola is not the profession it once was,” he conceded.

“It could be!” she scolded him. “My lord, how did we allow this to happen? I blame you and your cohort—but truly, I blame us, your elders, who permitted too many links in a sacred chain to corrode and fracture. It’s left you all free-floating, in crisis: buffoons in boats, morons with oars. Ignorant of your history. Ignorant of your potential. Without pride. Without purpose. And capable of expressing those insecurities only through outlandish public acts of idiocy. Before the eyes of an entire city, of the entire world, you are all being devoured from within by this ache for self-respect and meaning.

“So when you, Alessandro Munari, say you can’t believe that the gondolieri were powerful enough to vanquish the schifosi, this is why: Because you have lost all belief in the gondolieri. You have lost all belief in yourself.”

Alessandro felt flattened.

The adrenaline from earlier, on the canal, had finally dissipated from his body. He was scooped-out inside, fragile—gummed up with a buzzy residue of strange sensation. And now, the Magistrate had chastened him. The secret angst that moldered at his core, the dark globule of shame which he exhausted himself every day suppressing—she had held it up and shown it to him as blithely as though she were lifting a piece off lint off his shirt.

She was goading him to rearrange his understanding of himself, to enlarge his understanding of himself. Instead, he contracted into a defensive crouch.

“Bullshit,” he snapped. “What you’re telling me is bullshit.” And here, he’d pointedly abandoned the formal lei, downgrading to the informal tu. “The gondolieri would be ripped apart by those creatures! They’d be clobbered out of their boats by those tentacles. They’d be eaten and killed.”

The Magistrate met the younger man’s insouciant gaze and held it. Then, unperturbed, she inspected the smudgy nub of her joint and endeavored to take a final drag.

“Let me ask you,” she said, coughing quite a bit this time as she exhaled. “Again, you’ve studied well. Tell me, why all gondolas are black?”

“Enough of this ridiculous catechism,” Alessandro said. “Come on, you’re—"

“Gondoliero!” the Magistrate snapped. Her immaculate posture, undeviatingly straight until this point, now somehow straightened further. Her shoulders broadened. Her head ascended an additional inch above his. “Tell me. Why are all gondolas black?”

“A decree from the Doge,” Alessandro recited. “By the 17th Century, gondolas had become status objects among the aristocracy. The wealthy competed to make their boats striking and opulent, with an increasing array of bright colors and adornments. The Doge found this undignified. So he made a law: gondolas must be painted black—and only black.” Alessandro seemed to have come to the end of this narration, then added, hastily: “Six coats of paint.”

“Yes, that is the story. But again, the story is not entirely the truth,” the Magistrate said. “They were painted black because, the gondolieri discovered, the color black repelled the schifosi. It disoriented them, and therefore offered the gondolieri some small measure of protection. As did those.”

Alessandro looked down; she was pointing to the traditional black and white stripes across his sweater. He flashed back to the three creatures barreling toward his gondola hours earlier—his black gondola!—only to fork around him—in his striped sweater!—at the very last instant.

“Okay, fine. But how could the gondoliers possibly lure them into the piazza? You make those monsters sound docile, like a flock of sheep.”

“Oh, they were never docile,” she said. “But there were ways to encourage them. Tell me, what do you do when you row around a corner?”

“I sing. So other gondoliers will hear me coming—a tradition bastardized obnoxiously by tourists, who expect us to sing to them constantly on every ride. But traditionally, you would simply sing “‘o-e’” as you approach another gondola, or “o-e’ premando’” or “o-e’ stagando.’”

“Which means…?”

“Nonsense words. Derived from Venetian dialect, I believe. They are used to signify, ‘Here I come to the left.’ ‘Here I come to the right.’ They are—"

“That is what they’ve come to signify,” she told him. “But these were the calls your predecessors used to control the schifosi. The sound of their signing, the gondolieri discovered, had some mild, anaesthetizing effect. It weakened the creatures, making them just suggestible enough to be steered through the canals. And the fero da prora,” she went on quickly. “Tell me about that.”

“The iron blade attached to the prow of a gondola,” Alessandro said. The resentment in his voice was thinning, gradually diluted by an influx of wonder. “It functions to counterbalance the gondolier’s weight. Its shape is symbolic. The rounded arc at its top represents the Doge’s hat. The six points represent the six neighborhoods of Venice and—”

“A lethal instrument,” the Magistrate explained.

She produced, from inside the neck of her blouse, a wooden pendant in the shape of the fero da prora—an heirloom in her family for four hundred years. She made a show of fingering its six points, then turned them toward her and mimed stabbing at her own neck. “A secret emblem among a secret class of warriors,” she said. “A representation of the six-pointed spears used to slay the schifosi.”

Alessandro went silent. He’d been thrown into a kind of cognitive vertigo, rattled by the magnitude of his own ignorance, but also by the sheer richness of this history—a tapestry into which, without ever knowing it, he’d been snugly stitched all his life.

He and the Magistrate were now passing under the Sotoportego del Cavalletto, the ornate archway, and into the northwest corner of Piazza San Marco. The square was serene and silent in the moonlight. As they entered, it sprawled out before them like a flat stone sea.

Alessandro was accustomed to seeing the space infested with tourists, and with vendors hawking plastic fero da prora keychains and knock-off, polyester gondolieri shirts: bargain, Bangladeshi-made simulacrums of his culture.

But he tried now, instead, to visualize the piazza flooded with seawater, to internalize its furtive history as a kind of bloody colosseum. Enclosed by these same buildings, under this same Venetian night sky, generations of his ancestors had, no doubt, shaken off the same fear he’d felt during his confrontation with the creatures that night and worked, righteously, to slaughter them anyway.

“You see now how these protocols were encoded inside our Venetian culture,” the Magistrate said. “They were stowed away inside tradition and lore to ensure that they’d make safe passage from our city’s past into its future; to ensure that we Venetians would never forget—even if, over time, we ceased to remember.” Her eyes lifted past the gondolier and into the square. “They hid this secret knowledge in plain sight—even right above our heads.”

Alessandro turned. There, at the opposite end of the piazza, stood the square’s two iconic, towering columns—same as always, for all of Alessandro’s life and many centuries before.

But had he ever truly looked at them? Had he reckoned with, or even registered, their strangeness?

High atop the first stood a bronze statue of San Todaro, the patron saint of Venice before St. Mark—shown here with a writhing dragon at his feet. He was stabbing it with a spear.

And on top of the other pillar was, of course, the winged lion—the same chimera which appeared everywhere in Venice, always with this same splaying mane of thick, cylindrical locks encircling the base of its head, and the same pair of huge, powerful wings flaring off its back.

Alessandro shuddered.

The animal was a schifosi in disguise.

The Magistrate had continued walking, crossing the piazza toward her office behind the basilica, leaving Alessandro stupefied and alone at the other end of the square.

“Wait,” he called. “So what do we do now?”

Barbarigo stopped and cocked her head, befuddled. “Nothing” she said. “I can do nothing. Do you think that, given the danger, given the scale of destruction you witnessed tonight, to say nothing of the impotent degradation our city just suffered in defeat, that this situation still rests in the hands of an underfunded local ministry like mine? This isn’t even under ELAINE’S control now. Or Rome’s, for that matter. This is the EU. This is NATO. This is the Americans talking, most of all—with their petulant imbecile-in-chief who pounds his fist like a cranky, chunky child at mealtime and wants only the biggest, dumbest result right away.”

“Let that bastard whine,” Alessandro said. “Why should we listen to any of them? What can they do?”

“Anything they want! Everything they want. They’ve convinced Rome to evacuate the city in the morning and declare martial law. They’ll seize control of Venice as quickly as they can. Beyond that, nothing is off the table. Understand: two hundred Americans were killed at that museum—including their ambassador. A few billionaires’ children. A famous singer. A YouTuber of some renown. The Americans have an army base in Vicenza, you know. They have assets up and down the Adriatic. Then, there’s the UN Global Services Center in Brindisi—which is also Europe’s primary gateway to the Persian Gulf.

“The stakes are enormous. Just an hour ago, I listened as one government bigshot after another grew panicked, recognizing that this infestation could spread and choke off access to the entire Mediterranean. They want to stamp out the creatures here, decisively, before they’re forced to fight them everywhere! That’s the way these morons talk.”

“I don’t believe this. It is like a terrible movie.”

“It’s the military planners—they are already pushing everyone else aside. Before I fled to Dino’s, just to take a moment to bitch and drink, they were still arguing it out amongst themselves. Some want warships. Some want to lace the lagoon with undersea mines. Some want to lace it with poisons—chemical warfare in our lagoon! Can you imagine? They have even mentioned air strikes, artillery.”

“Bombs?” Alessandro cried. “This can’t be real. They would bomb Venice?”

“I can predict nothing,” Barbarigo answered. “They will do as they please. Venice is powerless. Its fate, always perilous, is now slipping out of our hands.”

She had raised her own fist and opened it dramatically to illustrate, like a magician revealing the absence of a coin. Then she paused, groggily examining her own fingers, smiling at the back of her hand.

“Ah, and now I’ve gone and gotten myself preposterously high!” Barbarigo said. “But it hardly matters. I have no role up there, other than to be patronized. The ‘Magistrate of the Waters’ sounds like a joke to these people. Like a renaissance wizard!”

Stepping onto the stoop of her office, Barbarigo now produced a flask from inside her coat and choked a quick dose of the liquid down.

Alessandro understood now: why, amid this crisis, she could spend so much time talking to an inconsequential gondolier like him. Because, she’d been rendered inconsequential herself.

An Italian soldier, cradling a machine gun, opened the door. Reaching for her flask again, the Magistrate looked at Alessandro and said, “All these years, I’ve worked to get that damn seawall in place just to give Venice a chance—a chance—to survive this unruly world. But no wall is high enough to hold back human foolishness.”

Before Alessandro could open his mouth to respond, the guard opened the door, and Barbarigo disappeared inside, stumbling slightly in her heels.

The guard looked indifferently at Alessandro and closed the door.

Millie stepped out of her apartment into the pitch-black doldrums of the early morning hours, nursing a bottle of Amarone. She wanted to see the city—to feel lost inside it—one more time.

Upstairs, her bag was packed. In about ninety more minutes, she would call Cooper from the first train to Rome and ask him for money for a plane ticket home. She rehearsed the conversation in her head. What if, by home, her grandpa thought she meant Florida and got excited? And, well, where did she actually mean?

Walking the desolate Fondamente Donde, she spotted a figure in the shadows and flinched with fright. The man was sitting on the cobblestones, against the far wall of a courtyard, facing a small, stubby bridge that crossed a narrow inlet of the canal.

“You again,” he said. It was Alessandro, the gondolier. “We are attractive.”

Millie managed an uncomfortable laugh. It was a weird moment to be hit on.

“Like magnets,” the gondolier clarified. “We are attractive. We keep snapping together.” He brought his palms together to demonstrate and kept them there, like a prayer.

Millie offered him the wine bottle. He declined.

He had not, for one second, moved his eyes away from the water.

“This bridge,” he said, motioning with his head, “is called the Ponte Diedo. It is one of the old fighting bridges. Many centuries ago, when families or working people in Venice had a feud, they would meet on certain bridges to fight. Very violent. They punched and punched each other until one has thrown the other into the canal. This resolved the dispute.”

“That's how it works in Florida too,” Millie said, smiling.

“My home,” Alessandro went on, motioning toward the building he was leaning against, still not turning his head. “I came to tell my mother to leave Venice, to warn her. But then I thought: she will be devastated, and she is old. I’ll wait for sunrise, at least. And so I am looking at the bridge all this time and remembering how much I worried when I was small. I worried about everything. I was a very philosophical child, with many complicated worries that overwhelmed me. And my father—he was a traditional, macho Italian man, a gondolier—he would lose patience with my worries and tell me always ‘Son, go to Ponte Diedo and have a fight with your feelings. Take your worries there, take your fear there, and knock them out’ And I did—I still go to that bridge sometimes when I worry. From him, I learned that sometimes a problem is not complicated: you must simply punch the bad thing until it drowns.”

“Seems like you should be on that bridge now.”

“I can’t.” Alessandro hoped he wouldn’t have to say it, but Millie wasn’t catching on. “Because… because the bridge is suspended over the water.”

The gondolier was scared to get close to the canal.

Millie sat down next to him. Her body ached from piloting the gondo and she hadn’t yet consumed enough of the wine to deaden the pain.

“They are taking Venice from us,” he suddenly told her, turning to look at her for the first time, his voice cracking with sadness.

“The animals?”

“No, NATO. The Americans. The world. They. There is always a they that acts on Venice as though it belongs to them. But this time, they are truly taking it from us. The Magistrate of the Waters says they are making plans right now. They will come to kill the animals, even if it means killing our lagoon or our city in the process. They are even mentioning bombs.”

Millie was thrown. She thought she’d inured herself to a certain species of anguish, that she could no longer be devastated by the knowledge that one more delicate facet of this world was imperiled. But there was something particularly poignant about this gondolier, this man whose unshakeable earnestness, that morning when he’d scooped her out of the Grand Canal, had stayed with her; who, fully cognizant of how irrevocably his city was disintegrating around him, seemed no less grateful to be part of it.

Millie didn’t want to admit it, but she’d felt some measure of that same sturdiness and resolve on the gondo that night. Fighting had liberated her—momentarily. But now, here they were: both of them crushed, exactly the same.

All of this, of course, would have been impossible to summarize. So, Millie simply responded, “I know how you feel.”

“No you don’t,” he shot back. “I am scared. I am grieving. I am despairing for the future of my city—my sanctuary, my womb, where the history of my family reaches back centuries, and centuries longer than the history of your whole country.”

“But I do feel the same way,” Millie said hesitantly. “I’ve always felt it, ever since I was a girl. It’s like my whole life I’ve been saying goodbye to the one place I belong—the only place I’ve ever belonged—and I’ve known there’s no way to save it. My Venice,” she said, “is Earth.”

A single tear had welled up in her eye and now ran along the ridge of her cheekbone. Alessandro lifted his finger and captured it, carefully, just before it reached her ear.

“You looked like a good fighter tonight,” he said, “a strong fighter, racing toward me in that silver suit, driving that—what was that? And where did you even get that costume? I did not know there was a superhero store here in Venice.”

“Shut up,” Millie said.

“But I want to say thank you. For saving me.”

“I didn’t do anything. The animals went right around you. Why did they do that?”

Alessandro took a deep breath. He began to relay the entire history of the gondoliers and ths schifosi that the Magistrate had revealed. He recited it with an aura of cool expertise which implied he’d harbored this secret knowledge all his life.

When he was done, Millie said: “Then it sounds like you still have all the tools you need to take the animals down. Do it again!”

“Ah, but these schifosi are different. You saw them! They may still respond to our singing or be disoriented by our black boats, but they are too ferocious for the gondolieri to fight at close range. Something in the environment has transformed them.”

“It’s the AquaStop, it’s—"

“The cocksucking wall,” he said. “The lagoon is dying.”

“Technically, the lagoon is changing,” Millie said. “Ecological change doesn’t mean death—not necessarily, not for everything… if that change is met with adaptation.”

“I don’t know,” Alessandro told her. “My ancestors slaughtered monsters in their gondolas. But to slaughter mutant monsters, you would need…?”

The air seemed to tauten between them; the silence swelled. Each wanted the other to say it. Alessandro said again: “You would need…”

“You would need…?”

“I am thinking: maybe mutant monsters could be slaughtered with mutant gondolas.”

“Gondolas with guns on them,” she said.

“Huge, ridiculous American gondolas with guns!”

Their back and forth accelerated; ideas started piling together.

“It would be a very strange plan,” Alessandro said finally. “But really, we are simply using your machines—what do you call them…?”

“Gondos.”

Alessandro laughed. The word sounded juvenile. “We are simply using your gondos in place of spears.”

Millie thought of Cooper again. She imagined him now, alone in the house with his trembling hands and regrets. This was precisely why he’d built the gondos: not to entertain a child, but as weapons—weapons with which to fight an enemy that no one else could figure out how to fight, except by obliterating the entire living landscape around it.

Which is to say: the gondos were designed as a weapon against human laziness, indifference, savagery, hubris.

And that’s exactly how they’d use them now.

“We’d have to do it right away,” she said, invigorated, “during the next big storm surge—before anyone else leaps in to carry out a different plan.”

“A storm is coming tomorrow night,” Alessandro told her. “A huge one.”

Millie stood up, walked to the middle of the bridge, stared down the long corridor of the canal for a moment, then threw the wine bottle as far as she could.

“Hey!” Alessandro shouted as it splashed into the water—the brazen littering just killed him.

But Millie was already dialing Guy Rondack.

“We have an idea,” she told him. “I think it will work. But I don’t know for sure.”

“Knowing is boring,” Guy said. “Meet me at ELAINE.”

A NOTE TO READERS, reiterated verbatim…

GONDOS will pause next week to give an influx of new readers a chance to catch up.

Then...buckle up as we binge all of Part Three, with the five final chapters of GONDOS released daily, Monday-Friday, October 7-11!

It’s going to be a balls-to-the-wall blockbuster event, as together we ride the lightning all the way to the end.

You won’t want to miss the stunning conclusion of…

GONDOS: THE NOVELIZATION OF THE MAJOR MOTION PICTURE GONDOS

Food has always been significant throughout history because of its universal value. The ideal item for our mutual benefit: https://basketball-stars.co/