The novelization of the major motion picture Gondos, serialized every Wednesday and Friday. For more information and to get caught up, click here.

Zendaya as Millie? Kristen Stewart? Channing Tatum as Guy? Share your Gondos casting ideas in the comments!

PREVIOUSLY…

A deadly creature with tentacles (or perhaps cerata) revealed itself. Not wanting to involve the Italian government, Lopez turned to Millie for help identifying the animal—then summoned hardnosed soldier of fortune Guy Rondack to neutralize the mysterious danger, once and for all.

They’d waited for the middle of the night, when the vaporetti stopped running and the city slumbered, when Venice was overtaken by an eerie and immaculate sense of desolation, and moving through the city gave one the same furtive charge as being in a museum after closing.

Guy Rondack coasted up the empty Grand Canal in a burly 24-foot aluminum-welded pilothouse boat—a pretty sweet craft that Lopez had commandeered with impressive swiftness from ELAINE’s military contracting division. Trailing him were three small skiffs.

“Charlie, Elio, Carla,” he called on the radio. “You’re going to be my alley cats. Break off into those smaller canals and let’s flush this rat out.”

The three smaller boats veered into different waterways, tunneling into the city’s interior. Guy had put two ELAINE security staffers in each: a driver seated at the stern, and a gunner holding a semiautomatic rifle with a silencer at the bow.

His plan was simple because the situation seemed so simple—and because Guy Rondack considered planning any more elaborately than necessary a form of gutless procrastination: The skiffs would coast through Venice until, eventually, the creature showed itself. And when it did, they’d fire at it until it was dead.

Guy cut his engine as he approached the Rialto Bridge. He’d hold this central position while the three strike teams made their rounds in case the animal tried to flee back down the Grand Canal and out to sea.

The Rialto was one of the city’s oldest and most recognizable landmarks—a low arch of Istrian limestone and white marble, topped by an elegant arcade of shops, spanning the narrowest point in the Grand Canal. It was said that thirty thousand selfies were taken on the bridge every day. But at this hour, with the weight of all those tourists off its back, Guy could almost hear the structure exhale.

He checked his watch: 2:20 AM. The last dishwashers would have just locked up at the Hard Rock Cafe near one foot of the bridge, and the first fishmongers and produce vendors wouldn’t arrive at the market on the opposite bank for another few hours.

Rondack rummaged through the cooler that some ELAINE lackey had left on board and stashed a can of beer in his jacket pocket for later, once the job was done. Then he had a seat and leaned back, watching reflected moonlight ripple across the underside of the arch, eight feet overhead.

Twenty minutes passed. Thirty minutes.

Just to the north, thick fog had started pouring through the city. It swirled low over the water, folding over itself like gauze. In a warren of narrow canals behind the Ca d’Oro, Carla let go of her rudder to lower her night vision goggles, wondering if they were now doing more harm than good.

She had insisted on going back out to search for whatever killed her boss. And though Rondack ultimately consented—he had only so many capable people to choose from—he wouldn’t allow her to be the one up front, with the gun. Instead, it was another young ELAINE employee standing there, boot propped on the prow, sweeping his rifle back and forth across the surface. He was swiveling back toward Carla to give a frustrated shrug—visibility was shit now—when an odd sound rushed through the water up ahead.

Guy had been tracking all three skiffs on his tablet: three blue ovals, coursing methodically around a satellite map. Periodically, he clicked back to another window, just to check that his boat’s sonar was still completely useless—scrambled by the centuries of debris heaped on the bottom of the canals.

Now, when he returned to the map, Carla’s blue oval was gone.

“Carla? Carla, come in.”

Nothing.

“What’s going on, Guy?” asked Charlie, one of the other team leaders. He sounded—Guy couldn’t help noticing—like a child, trying to be brave.

“Carla,” Guy said again, ignoring him.

Charlie couldn’t bear the long silence that followed. His voice was quivering this time: “Uh, it’s getting weird out here.”

“What happened to Carla, Guy?” This was Ennio now, in the third boat. He wasn’t even attempting to mask his agitation the way Charlie had.

Guy rubbed his temples. He’d worried about working with this junior varsity squad. It was a good thing they only had to kill a fish.

“Ennio, sit tight for a beat,” Guy said. “Take three deep breaths.”

He zoomed in on their locations. Charlie was far to the northwest, following a bend in the Rio de San Zuane. He’d passed into one of Venice’s thin places—a slot canyon in the built environment, where the canal squeezed down to half its previous width and, flanked by the high walls of the adjacent structures, turned nearly pitch black.

“Charlie, I’m bringing up your bodycams now—you and Ennio. I’m watching through your eyes. Tell me what’s weird. What are you seeing?”

“Something just feels… wrong,” Charlie said. He was whispering now. Another voice spoke off-mic—Charlie’s gunner—and Charlie added, “Natalia says it feels like we’re being hunted.”

Guy checked his watch again: two minutes and twenty seconds since Carla’s signal had disappeared. When he looked back at the tablet, Charlie’s bodycam feed had winked out, too.

“Charlie!” Guy said.

“What in the fuck!” Ennio blurted. “What happened to Charlie, Guy? What happened to Charlie?”

Guy watched Ennio’s video feed start to fidget and jerk; the young Italian had stood up at the rear of his boat and was moving around in a panic, scanning the canal. On the radio, he breathed heavily, muttering profanities, his English breaking apart under duress.

Guy stood up and grabbed the wheel of his boat. He’d go in after them.

But when he glanced back at the screen, the last camera feed—Ennio’s—shook violently and went dark.

The sound of Guy’s motor starting thundered under the low stone archway. There was a peculiar undertone in its echoing, though: a rush of white noise, like a fire extinguisher or a river, growing steadily clearer and more severe.

Guy scanned the console, trying to figure out what was broken. He cut the motor—but the sound remained.

It wasn’t his boat. It was behind his boat. And it was getting louder, bearing down on him fast.

Guy turned and saw it coming: a wide, boiling V at the surface of the water, plowing upstream in the dark.

Before he understood what was happening, and certainly before he could believe what was happening, something collided into the rear of his ship—a merciless thud, shoving him forward. He scrambled to restart his motor. A plume of something putrid suddenly splattered out of the canal behind him.

His propeller had sliced through part of the creature, spraying bloody globules of flesh into the air. His motor stalled, jammed up by the rest of the animal, which shook the boat again, undeterred.

Guy was stuck.

He reached for the firearm holstered to his leg. He leaned over the side.

It was directly underneath his boat now; he couldn’t really see it—only a blur of confused shapes spiraling into view and rapidly recoiling, slick with a purplish oil, almost luminescent in the moonlight.

He fired four times into the canal. The situation did not seem to change.

Suddenly, a second animal thwacked into the front of the boat. Guy was thrown ribs-first into the railing and onto the deck. The side of his head struck a mooring line on its steel cleat, stunning him momentarily and drawing blood. His gun, knocked loose, hurtled over the side.

The two creatures constricted, clenching the hull with such force that its aluminum began to bend.

Staggering to his feet, Guy initially thought he was dizzy. But the sensation wasn’t in his head. The boat was lifting.

Inconceivably, he was airborne—just slightly, but continuing to ascend, slowly rising out of the water as though on a hydraulic lift. Having fastened themselves to the keel of his boat underwater, the animals were now somehow rearing their bodies out of the canal to heave it aloft.

Fighting to keep his balance, Guy leaned over the railing again, as far as he could, but could not see much beyond the furious churning of the water.

The metal boat moaned as it lifted, buckling under the differential forces of the creatures hoisting it at either end. The railing Guy was leaning over began to twist and warp. He jumped back right before it snapped.

Now, the same sound surged in the distance again. And Guy saw signs of more of them approaching: a sprawling, foamy vortex bending the water, peeling up the center of the Grand Canal with impossible speed.

There had to be another eight or ten of them—twelve or fifteen. A herd!

They weaved and writhed in all directions as they swam, some carving erratic angles in the others’ wakes—though their overall trajectory was forward, unflinchingly forward, bursting straight up the very spine of Venice.

In no time, the sound of them crashing through the water turned deafening, reverberating off the bridge overhead. And, before Guy knew it, the animals were rushing directly under him and all around—a great migratory spasm, passing through.

He suddenly understood:

The first two had come to clear a path into the city, to lift him out of the way.

Guy Rondack was agog. Also, disgusted. He didn’t like fish, and an unbearable, briny musk now hung in the air—the heavy residue of the herd.

Meanwhile, the two under his boat were still lifting, steady as pistons. The space between him and the bridge was shrinking.

He was going to be crushed.

Guy searched for an escape route, some tool to seize on and leverage—when, suddenly, the rear of the boat shuddered and hopped.

The injured animal seemed to have momentarily lost its grip on the keel and readjusted. The stern plunged a few feet, and Guy skidded backward, struggling to replant his feet on the slanting deck.

He managed to grab one of the lines with both hands before being thrown off the side. But the rope uncoiled from its cleat, leaving him hanging flat against the hull.

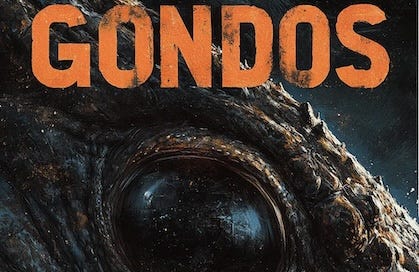

He was perfectly parallel to the animals now, only a few feet from the one at the stern. Its body was enormous—the shape of a walrus, thick as a bear, oily and tautened like one contiguous muscle as it worked to raise the boat. He saw the crooked gash his propeller had cut in its flank. And then, finally, he registered the madness of the arms.

Arms, tentacles, cerata—the reality of the things made the terminology irrelevant. Two colossal ones sprouted from the center of its back and stretched down the length of its body into the water, where they gyrated like frenzied turbines to propel its great weight out of the canal.

Guy’s eyes moved back up the body, to the mane of shorter tentacles streaming off the animal’s neck, all bulky as firehoses, gripping the bottom of the boat.

The creature had a snout like a dog’s, smeared with foamy mucus, and crinkling gills on its cheek. Another, nastier scar—a semi-circle of raised fresh—ran across its brow.

The boat kept rising. Guy could hear the roof of the pilot house splintering as the vessel met the bottom of the bridge.

The animal next to him was working with such focus and ferocity that it hadn’t noticed him hanging there.

No. That wasn’t why.

Slowly, the scar on the creature’s brow began to move.

It wasn’t a scar. It was an eyelid, stretching open.

Guy expected to see a pupil, or some striation of color in the eye, but this was it: this vacant black sphere—a bottomless dark disc that seemed to almost exert some strange, psychic gravity, to pull Guy in.

The boat crunched more violently into the bridge now, beginning to flatten. But as the animal became aware of the man helplessly suspended next to it, it released one of its upper tentacles from the hull and sent it coasting toward him, probing the space between.

Guy wrenched his body away from the arm. Recoiling, his elbow knocked into the beer can in his pocket.

A tool.

Hanging onto the rope with one hand, he pulled out the can and shook it.

The animal’s tentacle suddenly stiffened and, with unthinkable alacrity and force, jabbed into Guy’s ribs.

The blow sent him hurtling backward in a wide, wild arc on his rope. But then, swinging back toward the creature, he ripped open the beer can with his teeth and brandished it like mace.

The astringent spray flooded the creature’s eye. The animal screamed—a shrill and shattering wail—and the tentacle lashing at Guy a second time suddenly went limp.

Thinking quickly—no, reacting, because instinct is faster than thought—Guy tucked his legs as he continued swinging toward the animal and, pushing off its snout with one foot, let go of the rope and leapt into the air.

He was soaring through space now, alongside the bridge.

But he wasn’t going to make it to the bank. Not even close.

He twisted in mid-air, threw out his arms, and grabbed ahold of something bulging off the base of the bridge, just above the water line, then quickly found a ledge on which to rest his foot.

It was precisely at that moment that the two creatures, seemingly in fury, unleashed a sudden burst of force and gave the boat a final thrust.

The bridge shuddered as the boat crumpled against it. Guy could feel the vibrations in the rock. But the animals did not stop. He turned and saw them still heaving and heaving, until they’d punched the flattened vessel clear through the underside of the bridge.

There was a cacophony of cracking as the jewelry stores and souvenir stalls built atop the Rialto crumbled in on themselves and splintered. The creatures had now apparently vanished as quickly as they came, but the water roiled by their tentacles a moment ago was now splashing just as violently again, as hunks of ruptured marble rained down.

Guy could only watch it happen: the span splitting in two, its center dropping away—a landmark replaced by empty space.

Eventually, the clamor subsided. The debris field settled. Guy assessed his situation, clinging to one of the bases of the arch that remained.

The protuberance he was clutching was a relief sculpture—the head of St. Mark. And his foot was planted on the thick serpentine locks of a winged lion’s mane.

The big cat peered out menacingly from the bottom of the evangelist’s robes.

“Good kitty,” Rondack said.

Then he wiped the beer off his hands and began bouldering his way back to shore.

The sun rose over Venice a few hours later like stage lights going up at the start of another performance. But a central piece of scenery was missing.

The Rialto Bridge was gone. The iconic structure had been reduced to two useless stone stumps on opposite sides of the Grand Canal, hopelessly far apart.

As tourists entered the city, ripples of shock and fascination spread. Thousands of voices asked what happened, how such a thing was possible—whether this collapse was related to the collapse of that yellow palazzo in the news a few days ago.

And would it keep happening? Was it safe to be in Venice? Had the city’s alluring aura of decline all of a sudden passed through some terrible inflection point, into tangible hazard? And if it had, were these particular visitors cursed or blessed to be the ones who got to see it: this definitive beginning of Venice’s absolute end?

Other tourists, feeling entitled to see Venice and its many landmarks intact, only huffed and tutted, grimaced and whined, smarting incuriously from the personal injustice they’d been forced to bear. What the fuck? they asked their companions, tour guides and hotel concierges—and, it seemed, the universe itself.

Every single one of them went to see the ruin however. Foot traffic came coursing from every direction only to get bungled up at either end of the severed bridge—gawking at this extraordinary nothing where something had been.

They gasped. They swore. They pointed their phones at it and went live. Some lectured their spouses and children, or no one in particular (and with no particular expertise) about principles of civil engineering, the ineptitude of Italian builders, and the relative strengths of various types of stone.

“A barge blew up,” a few people said. And gradually, this explanation was transmitted up and down the procession of tourists, around and around. It was a shibboleth and catechism both: one man would say it—“A barge blew up”—and the one to whom he said it would repeat it back. The first said it with utmost certainty, to benficently educate the second, but the second responded as though it had been a question, and he were now authoritatively confirming it for the first.

“A barge blew up,” they kept saying. “One of those barges exploded. It was an explosion on a barge.”

This was not true. It was, instead, the cover story ELAINE had concocted after racing to the scene last night. There was no sign of Rondack, not even his body. But there was also no bridge, and this was, by far, the more urgent problem for the company to solve.

Lopez had come up with the story himself: a rogue barge traveling up the Grand Canal with a several thousand gallons of heating oil caught fire and exploded right under the bridge. Debris was impelled upward, busting straight through the marble, causing a collapse—a sucker punch knocking out the center of a smile.

And why in the middle of the night?

The oil merchants were illegal immigrants. It was black-market shit.

So that’s what Kristen explained when she placed the call to her contact in the city government, a man ELAINE was clandestinely paying nearly as much as they paid her: “We’re thinking: an electrical fire on board, or one of these blokes got clumsy with a Zippo,” she said. She assured the man that ELAINE would handle the investigation and deal with whatever bureaucratic mop-up required by Rome or the EU. “As always, we’re happy to take that off your plate.”

She was a virtuosic liar, smug enough to improvise flourishes for her own amusement. “I wish I had a more exciting story for you, Cosimo,” she added. “You’re free to tell the press it was a sea monster if you want.”

Now, all around the wreckage, the words were darting through the air, metamorphosing into fact.

“A barge blew up” the tourists said.

“A barge. It blew up.”

This was the scene Millie encountered at the Rialto that morning.

She’d been jolted awake before sunrise by a nightmare. She was swimming through an underwater grotto near her grandfather’s place back in Florida—until the cave walls started bleeding, and she realized she was actually passing through the hole in Oscar’s body.

She sat up sweating. She went for a run.

And now, in disbelief, as though thrown into a second dream, she let herself be absorbed by the river of tourists eddying at the base of the bridge, not-so-patiently waiting their turns to see.

Meanwhile, boat traffic piled up in the canal below. Millie watched the stupefied Venetians take in the ruin with hollow, grieving eyes, astonished not to see what they’d seen there every other day of their lives. There was one gondolier at the front of the pack, balanced at the rear of his boat with both hands on top of his head in shock, his face slightly quivering.

It was the gondolier—Alessandro, from the other morning. Millie squinted to make sure. He looked like was crying.

His gaze shfited. They momentarily locked eyes. Then Alessandro shook himself back to seriousness and rowed away.

Millie thought of the pride the gondolier had exuded—the familial connection he seemed to feel for these waterways, this landscape, this town. She looked around again, straining to see this preposterous panorama through his eyes: this crass scrum of giddy foreign mourners, cramming forward to get a better peek at the casket, still shopping for souvenirs and stuff to eat while stuck in line.

For four centuries, since the city’s decline as a commercial center, Venice’s primary business had been satisfying tourists: conducting the main-character energy of a hundred thousand protagonists every day.

“Venice’s chief function in the world is to be a kind of residential museum,” explained the book on Millie’s nightstand, on one of the 35 pages she’d actually read, “and though the city in summer can be hideously crowded and sweaty, the mobs of tourists unsightly, and the Venetians disagreeably predatory, nevertheless there is a functional feeling to it all, of an instrument accurately recording revolutions per minute, or a water-pump efficiently irrigating.”

Once, these visitors had only been able to enter Venice on the water, trickling in aboard gondolas, and thus forced to surrender to the civilized velocity at which the city naturally moved. But in 1841, a bridge was built, connecting Venice to the mainland, and the whole cadence of tourism intensified and changed. Now, every day in Santa Croce—Millie’s neighborhood, in the northwestern corner of the city—trains disgorged legions of outsiders six times every hour. Bus after bus pulled into a massive parking lot and—just like outside Disney World, or before a Monster Truck rally at the Superdome—an impenetrable throng of human bodies moved in unison toward the main event.

Venice adapted, attuning itself to these brutal new rhythms. Millie was watching it snap into place that morning, around even this cataclysmic disruption, this hole in the bridge: Vendors, artisans and street artists had seeped out of the city’s interior with their carts and easels, converging on the Rialto to capitalize on the crowd, while merchants at the little stalls along the Grand Canal opened their plywood shutters, revealing their wares.

Twelve hours earlier, every one of these shops had been depleted—trees picked clean of their fruit. But here they were, miraculously restocked to face another day.

The little wooden gondolas. The striped gondolier sweaters. The striped gondolier baby onesies. The gondola bath toys. The winged lion stuffed animals and keychains in pewter and plastic. The glass baubles. The lacework. The essentially single-use umbrellas and off-gassing, transparent ponchos to be snatched up in a storm. The rolled up Titian posters. The shot glasses. The soccer scarves. The lewd trinkets. The Piazza San Marco snow globes. The manic superbloom of t-shirts, all saying “Venezia” in different colors and fonts.

Millie didn’t have anything against the tourists; she was an outsider herself. The arrangement simply fascinated her—dispassionately, as a scientist. That morning, she contemplated this perpetual cycle of arrival, over-consumption and retreat in co-evolutionary terms: a finely honed symbiosis.

She understood the tourists to be migratory opportunists—an invasive species, mutated and grotesque. But the environment had also mutated, to meet their needs perfectly and therefore thrive.

This was Venice’s great trick: permitting that ravenous herd of grazers to tromp all over it and eat everything down to its roots—but then to make it all grow back, as lush as ever, by the time they returned.

Wait.

That was it—the Wonka. The manic cycles of die-backs and growth.

Wouldn’t that explain it?

Millie started running again, started sprinting.

She had to get to her lab.

…in CHAPTER 7!

“If we’re going to exterminate these things, we’ll need something smaller and nimbler,” Rondack said.

He pointed to the gondolier in the distance, plying the water between the crush of other boats with astounding quickness—weaving and swerving between other boats, getting exactly where he wanted to go.

“We need the warship version of that.”

Enjoying Gondos? Tell a friend and share your excitement on social media! Together, we can make Gondos a global sensation!!!