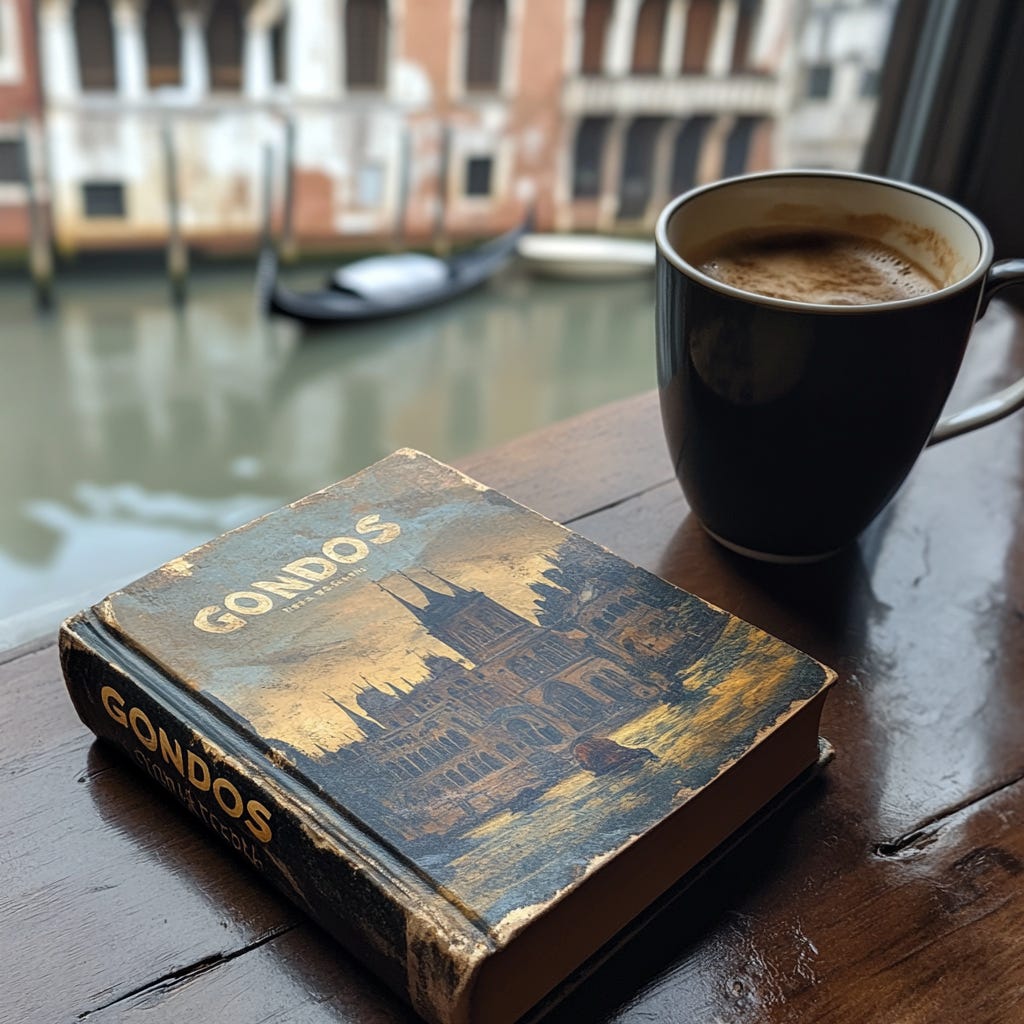

The novelization of the major motion picture “Gondos.” For more information and to get caught up, click here.

PREVIOUSLY…

Lopez poisoned the flooded piazza with Aspect H, turning every drop of water deadly. And things got even worse from there:

The skeefs, desperate to break through the gondolieri blocking the piazzetta and escape back to sea, began firing the toxic acid at the rowers. (Their tentacles were cerata after all!) Many men were burned, drowned or dismembered. Dino Simonetti was dissolved. Guy lost his left hand.

Millie, noting their predicament resembled the legend of St. Mark’s miracle, searched in vain for a similar solution and despaired.

But Alessandro appeared to find a mysterious glimmer of hope in a flickering candle, high in an apartment window overlooking the square….

Polonia Da Mugia was 89 years young. She was the proud product of a family that first arrived in Venice in the thirteenth century. The Da Mugias were fishermen, then dabbled in clockmaking, then started a metal shop in Venice’s Jewish Ghetto which fabricated—according to Polonia’s grandfather—the finest banisters and gates in all the city’s finest homes for three hundred years.

Life was prosperous—until the fascists came. Those bastards squeezed money out of Polonia’s family’s business as though they were juicing a fruit.

When the war was over in Europe, in April 1945, Polonia’s father leapt at the opportunity to travel halfway across the Italian peninsula to see, for himself, Mussolini’s body strung up in Milan. He took Polonia with him—hitchhiking two hundred and fifty kilometers each way. (The trains did not run on time that day; they had, in fact, ceased running at all.)

Piazzale Loreto was stuffed with people that evening, all crunching forward to get a look at the day-old corpse. Pushed to the front by her father, Polonia examined that wretched and rotund beached whale of a man and, without thinking twice, spit on his face. She was nine.

Her mother died the following year. Her father was never the same. Fortunately, a loving aunt stepped in to care for Polonia and advanced the girl’s education. Polonia grew to be one of the most sought-after seamstresses and embroidery artists in Venice. She performed miracles with thread.

At sixteen, she married a philandering doctor who was also a drunk. Once or twice, she spit on him too. But four years into their marriage, he was struck by lightning while hunting waterfowl in the lagoon, and Polonia quickly married a second time—to a sweet and diminutive electrician closer to her age who brought her flowers; who happily wore every garment she sewed for him, no matter the style or color; and who cried at the opera whenever they could afford to go. Polonia, in turn, lovingly listened to Georgio describe the new modern circuit boxes he was installing or how the wiring of a particular building had been chewed through by rats.

They were married for fifty-four years. Polonia insisted they were still married; it just so happened, unfortunately, that Giorgio had died. They had six children (two of whom died in infancy,) twenty grandchildren and forty-four great grandchildren, the majority of whom still lived and worked in Venice now. Although, as the city transformed, more and more moved to the mainland to pursue their careers. Many were electricians, having followed Giorgio into the trade.

Polonia disapproved of many of the changes she’d seen in Venice during all that time—particularly, the brash and unrelenting onslaught of tourists; how the homogenous culture of vacationing seemed, year by year, to overtake the traditional culture that drew the vacationers there.

She made these resentments known—often. If she saw young foreigners misbehaving, she didn’t hesitate to intervene. The other day, watching a petulant child pick his nose and smear the mucus on the wall of the Basilica of St. Mark—all while his parents just stood there, lost in their phones—Polonia had gripped the child’s wrist inside her own bony hand and scraped his fingertip across the wall to scour the masonry clean.

And the water? The rising sea? She detested it. The warming, the climate change—she would spit on the CEO of every oil company if she could.

She lived in the Procuratie Nuove—a magnificent, sixteenth-century apartment building on the south side of Piazza San Marco—in a second-story corner-unit that looked out on the whole piazza from one set of windows and down into the smaller, Piazetta San Marco from the other. Whenever Polonia felt sad or angry or lost, she would look across at the winged lion on its marble pillar and feel tranquil again.

Polonia loved Venice—she ached with love for her city, in fact. She loved its history and so many of its possible futures. But she worried about its present. She worried that this moment was a kind of fulcrum, like the hinge on a mouse trap, and that it was gradually swinging closed across the city’s throat.

That’s why, in recent weeks, she’d been disheartened to hear rumors from other old Venetians that the schifosi were returning. This too? Those beasts? On top of everything else? The other day, Polonia had explained this to two of her great-grandchildren when they met downstairs in the piazza for coffee. But they’d merely patted her on the head, not sure what the old woman was talking about, but assuring her that it was just a fairy tale.

Polonia, in turn, patted them on the head and told them this was the fairy tale: their gleaming modern world, with its handheld screens of digital shadow puppetry and its next-day delivery—its illusory stability that felt so secure. She told them to be careful on the canals after dark.

That night—that night of the monstrous storm and the monstrous tide, when the mayor and everyone else had kept telling her to evacuate, but of course she stayed—Polonia had sat at her window and watched the thunderheads gather over Venice. She watched the floodwaters enter the piazza. She watched that water rise. And when, eventually, the water rose so high that it knocked out the power out in the city, Polonia, still in her chair at the window, looked out window and suddenly felt alone. She felt like the only passenger on a very big ship adrift at sea.

Eventually, the weather started to settle. And that’s when they appeared—phantasmagorical and ugly in the yellow light of the low, gargantuan moon: two herds of sea creatures, filing into Piazza San Marco at the corner opposite her apartment, writhing like paper dragons in a parade.

Schifosi, she said aloud, to no one but herself.

Next came two people in futuristic uniforms, speeding around the flooded piazza on futuristic boats. Polonia checked her blood sugar. She wondered if she was hallucinating. But then the futuristic people were followed by a huge assembly of gondoliers, singing proudly in their uniforms to bring the animals to bay. Polonia exhaled when she saw the gondoliers. She did not feel alone anymore.

From there, she’d watched it all unfold like a stage play, invisibly from the window of her dark apartment on the square. She did not necessarily understand what she was watching, but she was rapt all the same. As the showdown escalated, she cheered for the gondolieri and applauded. She barked instructions at them–Duck! Go forward! Herd them there!–and she fretted once it was clear the monsters had the upper hand.

Now, with the gondolieri seemingly beaten back and beleaguered, with their human blockade at the piazetta being rapidly torn apart—with all seeming to be lost—Polonia had risen out of her chair to watch the two futuristic people and one of the gondoliers retreat behind those lines of courageous rowers and cower at the base of that pillar in the plaza.

What were they doing down there? Hiding? Taking a rest?

Fight, you imbeciles! Polonia shouted at the three of them from inside her apartment.

Exasperated, her eyes rolled up the pillar toward the winged lion statue at the very top. Suddenly, many disjointed memories and images snapped together in Polonia’s mind: the legend of the schifoso she’d been told as a girl; the gold pendant of St. Mark she’d never known her mother owned until she spotted it around her neck in her casket; the lightning bolt that struck her first husband dead in his boat; and Giorgio—sweet Giorgio—kneeling in a corner of their apartment, one long ago morning after a fearsome flood, merrily repairing all the washed-out electrical wiring, hunting for hazards, frayed ends and shorts.

And all at once—in a flash—Polonia Da Mugia knew how to help.

She was not, at 89, a strong woman. But now, as she fetched a candle to light her way through the apartment, some dormant force inside her body was rising, ready to be expelled.

She started by dragging the two heavy bronze lamps from either side of her sofa to the window. She lugged the air purifier out of the corner and set it there too. She went to her little laundry closet, gathered up all her longest extension cords and power strips, then retrieved her blow dryer and curling irons from her bathroom, her blender and toaster from her kitchen, and her alarm clock from her bedside table, and placed them all at the window too.

She plugged everything in, strung it all together. She grabbed a skillet and big metal spoon from the kitchen and got that ready too. She cranked open her window open and started banging the skillet, making as much noise as she could, trying to rally whomever else might have been silently hunkered in the surrounding apartments, who’d been watching this tragedy unfold in the piazza too.

Then, Polonia started heaving all of those electronics, piece by piece, out the window and into the water below.

Up your ass, schifosi, she chortled under her breath.

She alternated between banging the skillet and throwing stuff. And soon she noticed two neighbors with their faces pressed against the glass.

Come on, come on! she shouted at them. She whirled her hand through the air to get them going until she could tell from their faces that they understood.

Just then, a flatscreen television splashed into the water from the apartment directly above her, trailing a long extension cord, still plugged in upstairs.

A second splash: a microwave oven.

A man with a mustache appeared in a different window. He tossed an electric kettle, followed by a vacuum, two more televisions and a space heater.

More devices were tumbling down now. At the apartment building directly across the piazza, other windows were swinging open, disgorging appliances, too.

Polonia kept banging her skillet as hard as she could, her rickety arms almost spent.

But in fact, no more encouragement was necessary.

What Polonia had started had already become unstoppable: a monsoon of machines, flying from all directions, all still plugged in—a message she prayed would be decoded by those on the battlefield below.

Hunkered in their gondos at the base of the pillar, behind the increasingly brittle wall of singing gondoliers that barricaded the piazzetta up ahead, Millie and Guy turned their heads in bewilderment—searching for whatever Alessandro had been staring at, and from which he still couldn’t pull his attention away.

Around the square, the austere buildings were springing to life in the dark. Windows were opening. People were yelling. Objects were raining down.

“Where’d all those people come from?” Guy said, kneeling with his medical kit at the back of his gondo, bandaging up the rawness where his left hand had been. “I thought the city was evacuated.”

“They were all too proud to leave,” Millie said.

“Fine, but what are they doing?”

Alessandro still had his back to them, staring up in silent fascination. He was overcome by the sight of it: the extension cords and appliances cascading out of the apartments, splashing into the water below. It truly felt like witnessing something miraculous—the collective action of hundreds of saints.

“Don’t you understand?” he said quietly. “They are sending down their energy. They are putting wires into the water. It’s a message. They are telling us to turn the electricity back on.”

“Because water conducts electricity…” Millie murmured, catching on.

Now, Alessandro finally turned back to face them. “It is like the story,” he said. “The Venetians are showing us how to make a lightning strike.”

Guy was already fiddling with his radio. “Theo,” he said. “Come in. We need to get the electrical grid back on—now.”

“Guy, there’s still six feet of water in the city.” Theo said. “That entire piazza is one huge saltwater circuit. If we force the power back on, you’ll have current racing through it everywhere like a bolt of…”

“Perfect,” Guy snapped.

“Oh shit,” Theo said. Electrocution. It was a brilliant idea.

“Exactly,” Guy huffed. “Our special tonight is deep-fried skeef.”

Guy paused; it was a killer little quip, he thought. But Theo didn’t react. He was busy calling up schematics from Venice’s electrical utility and hunting through those diagrams as fast as he could. “Stand by. I think I can probably supercharge things for you… Okay, yeah. There’s a large, freestanding transformer box fifteen meters behind you: southeast corner of the piazzetta, right at the lip of the Grand Canal.”

“And…?” Guy asked impatiently.

Just then, there was a riot of anguished screaming on the front lines. Enough time had passed for the skeefs to absorb more of the acid and they were now unleashing another volley of it back at the blockade. The gondoliers scurried, then quickly reclosed their ranks.

Eight more had been hit. Five others fell in.

Millie peeled off through the water to back them up.

“Bust the transformer open,” Theo explained. “Just rip it up inside. It shouldn’t be hard—you just need to get the wiring in contact with the water. That box pulls five hundred kilowatts from an undersea transmission line. It’s going to be a hell of a jolt.”

Alessandro was already hailing two gondoliers, dispatching them to locate the box.

“We’re on it,” Guy said. “Stand by to switch on the power.”

“I can’t,” Theo said.

“What do you mean?” Millie erupted over the radio, fits of gunfire clattering behind her.

“It has to be done manually. It’s complicated, but I basically booby-trapped the entire grid to make sure that Russell couldn’t take back control after I hijacked the wall.” It was clear from the quaver in Theo’s voice that he regretted it; it had seemed clever in the moment, but it was overkill—a flourish, a flex. He hadn’t really thought through the consequences. “Everything’s routed to a manual switch at the seawall’s operations center.”

“You’re in the operations center,” Guy said. “Hit the switch.”

“I’m in the command center,” Theo said. “The operations center is in a lighthouse at the northern terminus of the wall. Sector D-19. You’ll have to turn it on there.”

Guy exhaled. “Millie, you getting this? You have to be the one who goes.” Then, in case she was inclined to waste time arguing, Guy choked down his pride and added: “I can’t do it. I’m hurt.”

“But that’s fifteen miles from here,” she radioed. “It will take—”

“Go,” Alessandro told her. “It will be much faster than waiting for this water to drain.” He clasped his oar, ready to row back into battle. “We gondolieri will hold them as long as it takes,” he said.

They all wanted to believe him. But the skeefs were taking out more gondoliers every minute; it was only a matter of time before they ruptured the formation altogether and surged through. “I promise you,” Alessandro said. “We can do it.”

“No,” Guy said. “We can do it. Together.”

He rose unsteadily to his feet. He reached over to Alessandro and removed the red handkerchief from the gondolier’s neck. Then, using his one good hand and his teeth, Guy tied the handkerchief around the wound he’d just bandaged and cinched his injured wrist to the rudder rod of his gondo—essentially cuffing himself to the vehicle. Then he got in position to pilot the craft, gripping the throttle with his right hand and guiding the rudder back and forth with the arm that was bound to it. He cringed from the pain. But he could still manage to steer.

“Yes,” Alessandro said. “Together. Gondo and gondoliers.”

“And I can help too!”

Guy and Alessandro turned toward the voice. They hadn’t noticed her coasting into the piazza from the Grand Canal right behind them: the Magistrate of the Waters, standing at the front of a black gondola with exquisite gold ornamentation, rowed by a graceful young woman at its stern.

The Magistrate wore all black: a full-length Prada raincoat and a long leather skirt, the slit of which splayed open to reveal a glimpse of her bare thigh as she rested one foot on the prow. The toe of her leather boot pointed forward, aligned with the gleaming fero da prora at the tip of the boat.

Her posture conveyed both complete authority and unrelenting glamor—an Italian Washington crossing the Delaware in knee-high Louboutins.

“May I?” she asked Alessandro, commandeering his bullhorn.

She nodded to her rower and proceeded, approaching the wall of gondoliers from behind.

“Buona sera, ragazzi,” she shouted. “My first sentinels and guardians! Please, help me sing a song that’s as goddamn sexy as all of you.”

Guy said into his radio: “We’ve got this, Millie. Go.” And after firing a few last rounds at the rampaging skeefs, she twisted her gondo around and tore off.

As Millie buzzed out of the piazza and down the Grand Canal, she could hear the Magistrate’s voice in the bullhorn leading the gondolieri in song—and all the men joining in, belting the Italian lyrics with renewed intensity, as they battled to stand their ground.

Though the tune was familiar, Millie couldn’t place it; she couldn’t understand the words. But just as she was passing out of earshot, the gondoliers’ voices switched to English and swelled into the chorus:

“All the young dudes, carry the news.”

Soon, Millie was rocketing out of the mouth of the Grand Canal and crossing the open water of the lagoon. Her gondo ripped through the tide—a small, black blip shooting through the spotlight of a swollen moon.

For the first time all night, she was alone.

Time collapsed in on itself as she traveled. All the emotional material of her life somehow smeared together and fused. She was, at that moment, in Italy—but back in the Everglades, too. She was a twenty-nine-year-old woman on a mission to save Venice, and also a carefree teenager, joyously careening between barrier islands with the twins. She was a little girl undone by the sight of ibises, sputtering drunkenly in a poisoned swamp—birds trying to fly but unable to lift themselves off the ground. And she was a small, scared child abandoned in the house of a strange, old man.

Overhead, the storm clouds had cleared. The air settling into Venice was clean and calm. And yet, the water still seemed furious.

Millie gripped her gondo’s controls with all her strength to fight the chop. She only now realized that her leg had been cut open somehow below the knee. Blood leaked through her flight suit. And each time her gondo slammed up and down in the water, the pain made her wince.

Soon, a segment of the AquaStop appeared directly ahead of her: a dark colossus. She’d never actually seen the thing upright in person before, she realized—only watched it rise in computer simulations.

Banking left, she traveled along the length of the wall until she reached the lighthouse: a squat, steel pentagon, like a military watchtower, with a ladder bolted to the side.

“I’m here,” she told Theo, leaping off her gondo and scrambling up the rock slope at its base. “What do I do?”

“You’re inside already?”

“Almost, I’m climbing,” Millie said with a grunt. Her injured leg wobbled out from under her on the ladder. She caught herself. She caught her breath. She tried again.

The tiny room into which she eventually hoisted herself was cluttered with analog control panels and switches.

“What am I looking for?”

“It’s a big lever. You can’t miss it. Right side of the main console—eye-level.”

Millie saw it. It looked like a huge emergency brake. She wrapped her hand around it, making a fist.

Then she hesitated.

Right above the lever was a narrow window—and, just then, the moon happened to be perfectly centered in the glass. Millie saw it there and blinked. And, in the millisecond her eyes were shut, she realized that she was about to detonate a kind of bomb.

Pulling that lever would send electricity forking through the canals—and some great distance through the lagoon as well: a severe burst of obliterating energy, indiscriminately undoing the natural order wherever it went.

The ultimate ecological consequences of that blast could be relatively minor or catastrophic—or anywhere on the spectrum in between. But there definitely would be consequences: unintended, unconsidered, unforeseen. She would be destroying some portion of what made this planet resplendent and alive.

Millie’s eyes opened. She saw the moon again: smoke-gray, barren, strange. Its starkness was a reminder of how implausible this other place was—this wisp of precious material wafting through space.

Millie had never done anything so reckless in her life. But she had never done anything so necessary either.

“In five,” she said over the radio, and started counting down.

Back in the piazzetta, under the watchful eye of the winged lion on its perch, the blockade of singing gondoliers was rapidly deteriorating, just barely holding at bay the throbbing, explosive tangle of monsters as the water drained. And yet, as the Magistrate and Alesandro rallied them through the very same song for a fourth or fifth time, some of the men seemed re-enlivened, even wailing the guitar parts with their mouths.

Shades of an odd euphoria—camaraderie in wartime—had seized them, a psychic immune response to the horrors all around. They locked oars in resistance, as the accelerating current joggled them backward, juddered them around. Some sang arm-in-arm behind the upturned or capsized boats of their fallen brothers, which they had swept toward the center and piled into a barricade.

Many good men had died.

The rowers Alessandro had dispatched to bust up the transformer box signaled that they’d done their job—just as the skeefs, enraged, sputtered Aspect H from the tips of their tentacles again. Five more gondoliers went down.

Alessandro pumped his fist at the lines of singers, shouting over their chorus: “Hey dudes! I want to hear you!”

“Carry the news,” they belted back. “Boogaloo dudes….”

Guy, meanwhile, was careening in and out of the fray, handling his gondo’s rudder inelegantly with his injured arm, but somehow managing, despite the pain, to evade every tentacle that reached for him, to skirt the pulses of poison that kept raining down.

He was in the process of gunning down a trio of skeefs, in one lethal pass, when he heard Millie’s voice start counting down on the radio. Suddenly, he eyed the gondo under his feet with dismay.

“Three,” Millie said.

The gondolieri would be fine—Alessandro had understood this: their wooden boats would not conduct the electricity. But Guy was speeding through that flood on a huge block of metal.

“Two.”

He spotted Alessandro’s gondola straight ahead and sped toward it at top-speed, simultaneously working his throttle and pushing all his body weight down onto the rear of the boat until—

“One.”

All of it happened together in an instant:

The front of Guy’s gondo lifted. The vehicle soared out of the water.

Airborne and still rising, it reached the top of its gorgeous arc—just out of reach of a gargantuan skeef which had, just then, breached straight out of the flood to lunge at Guy mouth-first.

A horrible buzzing rang through the piazzetta—a rattling, deafening zap.

The charge could be heard before it was seen. It registered next as a feeling: a queasiness shuddering through everyone’s stomachs, a bristling through the hair on their arms.

That was followed by a bright white shock of light, flaring omnidirectionally. It flashed off every pane of glass in the surrounding buildings, off the mosaics on the basilica, off the bronze winged lion overhead. Only when it struck the absolute black of the skeefs’ eyes, raised above the water, did that light get fully absorbed and not ricochet back.

The animal under Guy’s gondo suddenly convulsed and collapsed back underwater. An atrocious scent—a plume of charred muscle—wafted upward in its place.

Still in the air, Guy shook his bandaged arm free from the rudder rod behind him and leapt off his gondo—flailing through the air for several seconds and…

…crashing with a blunt thud onto the bench at the center of Alessandro’s gondola, where the gondolier hoisted the warrior to his feet and embraced him.

Guy had been blinded momentarily, but rubbing his eyes, it all came into focus: the hundreds of scorched, bulbous bodies bobbling at the surface, pulsating with residual shocks. Around the carcasses, a red mealy residue coated the water. A few tentacles twitched, tangling together, stiffening up.

“First sentinels and guardians!” Alessandro screamed, rearing his head back, his hoarse voice somehow expanding to fill up the square.

The gondolieri erupted all around him, raising their arms, unloading their own potent cries of catharsis—of triumph, of glee. They knocked their oars against their hulls to applaud the Venetians in the windows. The Venetians banged their pots to clap back.

Quietly, on the periphery, the Magistrate of the Waters smiled and, removing a joint from her pocket, motioned for her rower to exit the square.

Meanwhile, in the operations center, Millie mistook the anarchic celebration on the radio for wails of suffering and dropped to her knees. She still had her hand around the lever when she heard Guy’s voice break in.

“You got ’em, Millie. We got ’em. It was beautiful. The piazza looks beautiful! Come back and see.”

By the time the sun rose, the flood had completely receded and distended skeefs littered the dry brickwork of Piazza San Marco like boulders.

Their charred snouts were crusted with sea salt and debris; their startled eyes, cleaved open; their pulpy, fetid tentacles splayed around them like funerary wreaths. Ridges of blubber shivered in a stiff, southerly wind.

Beached, the skeletons struggled to support the creatures’ body mass outside the water. One by one, the carcasses began to slump in on themselves—to crinkle and warp, then finally collapse. Putrid gas was expelled from the gills. Wounded pockets of flesh tore open further or burst.

Environmental ministers from the European Union swept in immediately to evaluate the site. They’d been outraged by reports of ELAINE’s unilateral and unauthorized use of a chemical agent and detained Russell Lopez right away.

And yet, the first wave of technicians quickly determined that the bulk of the Aspect H released into the piazza that night had been absorbed by the skeefs’ cerata and was remained sequestered in their tissue. Adverse effects from the poison to the surrounding ecology were not likely to be severe.

This also meant the skeefs themselves were now hazardous waste, and swiftly classified as such. Complex designations and international protocols snapped into place around their remains. Yellow tape was strung around every carcass. Hazmat crews were on their way to Venice to dismantle the bodies and pile the pieces into airtight drums, which would then be carted away on railcars and buried at a secure site.

And yet, there was a window that morning before all this happened, before the bureaucracy had reasserted itself and—in the ecstatic, dreamlike aftermath of the disaster—hundreds of jubilant Venetians trickled into the piazza from around the city to take a look. They congregated freely at the center of their city, celebrating at all by themselves.

There were still no outsiders in Venice. The barricades erected the previous morning to shut the city down were still in place and, oddly, this privacy gave the Venetians permission to behave like tourists. They posed in front of the slain skeefs and snapped unceasing sequences of selfies—grinning widely, embracing, kicking the animals’ jaws and flanks. And they rushed to have their pictures taken with the gondoliers with even greater glee.

The rowers had all stuck around: haggard-looking, bloody, singed and soaked. But they held their heads high as they posed with women and children, with men twice their size. Arms from all directions kept slinging over their shoulders, slapping their backs, drawing them—instinctually and without self-consciousnes—into the same repertoire of poses the tourists loved: Peace signs. Flexed biceps. Ninja kick. Hands clasped over heads like Olympic champions. Cheeks squished to cheeks. And of course, double thumbs up.

“They really don’t know how much they’re embarassing themselves, do they?” Guy told Millie, as the two ambled through the piazza anonymously, taking it all in.

“They’re carefree,” Millie said. “You and me should try it some time.”

Guy let that sink in.

“You know,” he said, “if this were the end of an action movie, I’d kiss you right now.”

“That’s probably true.” Millie’s body language wasn’t allowing it. But her mind wasn’t ruling it out entirely.

“So what do you do now?” she asked him. “Rush off somewhere else to pick another fight?”

“Nah. I was thinking: It’s not like I haven’t had my share of adventures before. But for the first time, I feel like I might actually have a good story to tell about it. I can’t figure out why, but the way this all unfolded feels meaningful—something I should write about.”

They turned to watch a cluster of gondolieri whooping behind them. The men had put one of their striped sweaters on a little girl. The garment hung over her body like a blanket. Alessandro lifted the child onto his shoulders, bobbing her up and down and posing for more pictures while the other gondoliers screamed and saluted her: a Magistrate in training, or maybe, one day, a fellow gondolier.

“It was just a different kind of battle,” Guy went on. “It surprised me, I guess.”

“You’re a writer?” Millie said.

“I’d like to give it a shot.” He looked down at his bandaged wrist, then raised the other one to show her—his writing hand. “I’ve still got all the tools I need.”

Millie swept a lock of hair away from her face to make sure he saw her smile.

“And you?” he said. “Where are you heading?”

“Florida. I have some unfinished business there.”

“With Cooper,” Guy said knowingly.

“With Cooper, yes. But I mean, out on the landscape—in the Everglades. There are some fights I picked as a kid that I think I gave up on prematurely.”

“Well, let me know if you need some muscle,” Guy told me.

“I think I might,” she said.

They turned to take one last look across Piazza San Marco. It was a gorgeous view, just like everyone kept saying it was: one of the most awe-inspiring in all of Europe. Even with the damage to the basilica’s facade. Even with the silt and dross and debris tracked everywhere by the flood. Even with hundreds of dead monsters heaped across the pavement.

Millie knew they hadn’t actually saved the city. It was still sinking, still drowning, still succumbing to the chaos that enfolded it and escalated every second of every day.

Venice was dying—beset by entropy on all sides. But in that sense, Millie told herself, it was no different from the rest of us. We are here on Earth to push against all that—to defend the present and to protect the future for as long as we can.

Impermanence is the natural order. Every moment of our existence stands in defiance of it. To live is to fight.

Millie was about to share this epiphany with Guy—to attempt to explain it all to him somehow—when he put his arm around her. Instead of talking, she closed her eyes and leaned in.

Epilogue

Also circulating inconspicuously through the crowd in Piazza San Marco that morning was a curious little man in glasses and a heavy tweed coat.

The man, a zoologist from a university in Rome, had driven toward Venice overnight then paid an exorbitant amount, in cash, to a barge-owner in Fusina to shuttle him the rest of the way across the water, sidestepping the government’s blockades.

The man carried a small attaché case in one hand and a folio of documents in the other. The latter contained eighteen pages of hastily obtained permits, licenses and countersigned forms which the man had imagined being asked to present again and again to authorities, at various checkpoints or barricades, once inside the city. But he hadn’t been stopped by a single officer since he’d arrived.

He made his way to one corner of the piazza, near the Doge’s palace, and knelt beside one of the carcasses. Working quickly, but with precision and care, he donned a pair of latex gloves, removed a plastic pouch from his inside breast pocket and a sterilized scalpel from out of the pouch. He used the tool to slice a small, tender rectangle of flesh from the animal’s side.

The man held the sample up to the sun to examine it momentarily. Then he deposited it inside a glass container and twisted the lid shut.

He opened his briefcase. Vapor rushed out—dry ice, to preserve the sample on his trip back home. He secured the glass container in a special compartment of the briefcase and locked the clasps.

The man crossed the piazza again. He traversed the city and boarded the first train out of Venice, as soon as service resumed.

He was exhausted. But he was never able to sleep on trains. So he read, stretching a newspaper like a curtain between himself and the rest of the world.

Eventually, a ticket agent moved through the car. After punching the man’s ticket, the agent accidentally kicked the man’s briefcase, which he’d stowed right beside him at the edge of the aisle. The ticket agent gave the man a dirty look, but the man had returned to his newspaper and did not see.

Three rows back, seated on the aisle on the opposite side of the train car, a seven-year-old boy stared absentmindedly ahead. It took a moment for him to consciously notice the strange motion of the briefcase on the floor in front of him—and then, a moment longer to realize it was true: the case was actually moving, independent of the rumbling motion of the train.

The boy watched the briefcase hiccup and jerk. He watched it hop a few millimeters off the ground.

The boy tugged on his father’s forearm and pointed. But his father was busy texting, rampantly sending dispatches to friends and relatives about everything he’d so far gleaned about what had happened the night before.

Without looking, the father handed the boy an iPad. It was still three and a half hours to Rome.

The boy glanced at the tablet. He glanced at the jittering briefcase in the aisle. Then, losing interest in both, he turned to face the window and watched the golden winter wheatfields and endless valleys of the Veneto whir by.

The view from the train was beautiful, and there was so much to see.

The landscape was transforming before his eyes at very high speed.

THE END

Thank you for reading GONDOS: THE NOVELIZATION OF THE MAJOR MOTION PICTURE GONDOS.

YOURS TRULY,

JON MOOALLEM

Bravo!👏🏼